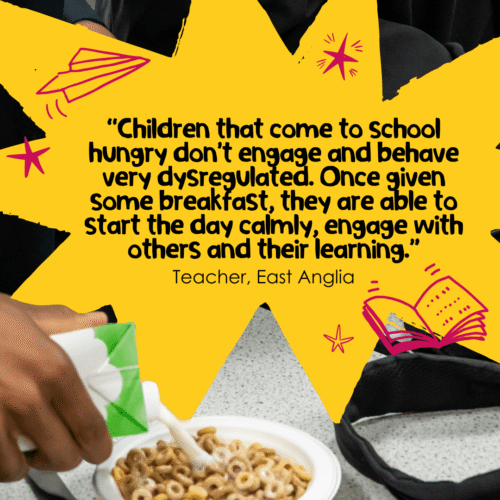

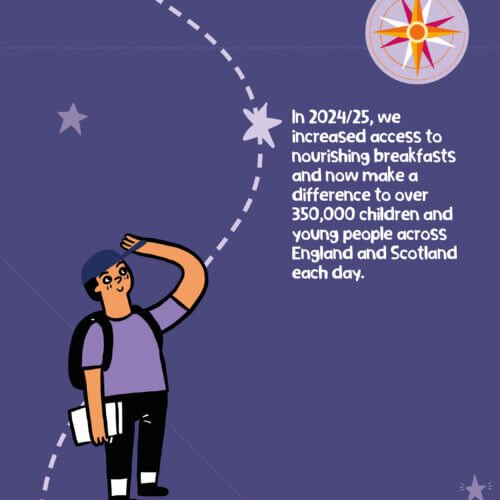

Having breakfast at school makes a big impact across a child’s education.

Our impact- What we do

Having breakfast at school makes a big impact across a child’s education.

Our impact - Get involved

Breakfast Powers Opportunity

Take action here - Schools hub

Want to become a Magic Breakfast school? Sign up today!

Get on board - News & Views

- About

Want to hear more? Sign up to receive an extra slice of Magic Breakfast in your inbox!

Email updates

![[He] didn’t know how to butter a bagel six months ago, now he's making bagels for the whole class.](https://www.magicbreakfast.com/wp-content/uploads/RS3276_DSC03425-e1760108621955-500x500.jpg)